I took a closer look at the adaptations of this woodpecker to its feeding and nesting habits. Most woodpecker species have a chisel-shaped bill for digging into wood while the Northern Flicker has a slightly curved one for removing ants from the soil surface or cavities in the ground. Woodpeckers have barbed, sticky, extremely long tongues which reduce the amount of excavation required for foraging and reach deep inside crevices and insect tunnels. Tree-feeding woodpeckers have prominent nasal tufts to protect the nostrils from wood chips but, since the Northern Flicker rarely chips wood (usually to dig its nest hole) it has reduced nasal tufts.

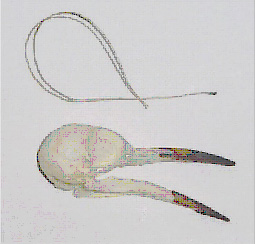

Skull and tongue of the Northern Flicker with permission from Kidswings.com

The long extensive tongue of woodpeckers, like that of hummingbirds, is made possible by the greatly elongated hyoid apparatus, a set of bones and muscles that controls tongue movements. In the Hairy Woodpecker this hyoid apparatus wraps around the entire skull and coils around the eyes. When extended, the tongue of this species can reach five inches.

Woodpeckers have two toes forward and two back but in many instances as the bird is climbing the outer rear toe rotates to the side allowing them to securely grip bark. The central tail feathers are curved and stiffened with rigid points that flex when the tail is pressed on the trunk giving a spring-like anchor as the third point of a strong triangular base for leverage to hammer into the wood.

The bird uses this base to rock back and forth rapidly beating its beak against wood bark in the familiar staccato. The molt pattern of the tail is adapted to maintain the climbing function: the all-important central feathers are not dropped until the other tail feathers have grown to full length; then the outer feathers can support the bird during climbing while the central feathers re-grow.

The brain case is enlarged and the frontal bones are folded at the base of the bill to act as shock absorbers and muscles behind the bill do similar work, hence no headache.

It did not help to discover that my self-appointed alarm was pulling his punches. He used only his head and neck muscles to drum on the roof metal to attract a mate, if he had used his whole body and springy tail, as when drilling into a tree, I would have had a much ruder awakening.

Back to ... Mendocino Coast Audubon Society Newsletter Articles | Home page